Graham Fawcett

photo: Birgitta Johansson

writer, teacher, translator and broadcaster

e-mail: [email protected]

Graham Fawcett at The Poetry School

During seventeen very happy and fulfilling years (1998-2015) as a tutor for the Poetry School, Graham provided a link between Poetry School groups of poets and readers on the one hand and, on the other, the significant books of the poetry canon worldwide in English and translation and from antiquity to the present.

He wrote and taught poetry courses of between 10 and 30 weeks designed to encourage the reading of poetry past and present from around the world.

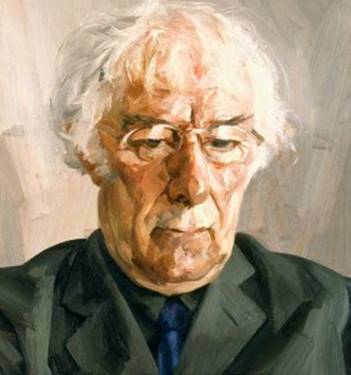

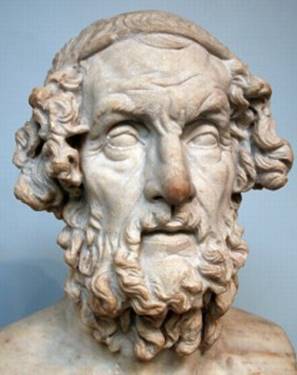

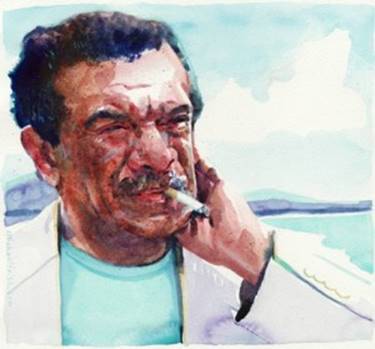

Heaney to Homer and Back (30 weeks)

Heaney, Lorca, Rilke, Cavafy, Dickinson, Baudelaire, Pushkin, Leopardi, Milton, Shakespeare (poems), Dante, The Nibelungenlied, Early Chinese Lyric Poetry, Vergil, The Kalevala,

Homer, Horace, Ovid, Beowulf, La Chanson de Roland, Chaucer, Camoes, Whitman, Yeats, Wallace Stevens, Pound, Akhmatova, MacDiarmid, Neruda, Walcott

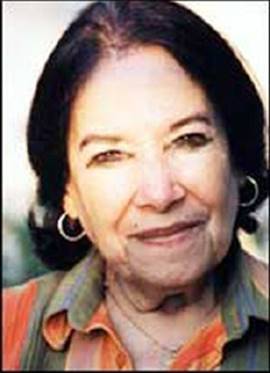

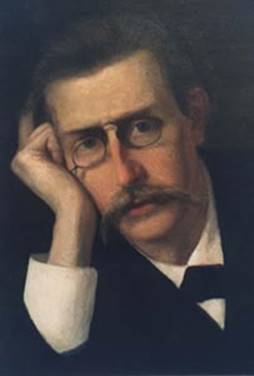

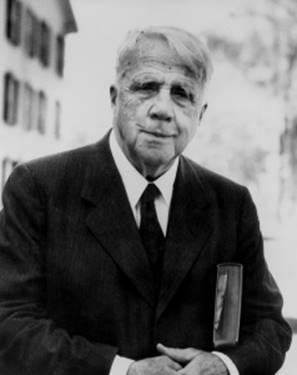

(Images: Seamus Heaney, Homer, Derek Walcott)

It was during 1996 that Mimi Khalvati asked me if I could come up with an idea for a reading course to help launch the about-to-be-created Poetry School. 1996 had been an Olympic Games year and at the time I had been researching a week’s trip to Western Sardinia to write a piece for the Telegraph which would cover the famous L’Ardia horse-race at Sedilo in the province of Oristano. In that race, hundreds of bareback riders hurl themselves and their steeds down the hill from the village to the sanctuary of St Constantine at the bottom, and then process slowly seven times round the sanctuary’s church. This round-and-back climax of the race put me in mind of the original Ancient Greek Olympic Games circuit, with its sharp turns around posts at either end of the track, and reinforced for me the idea of a lap as a going out and coming back. I felt sure that the new reading course should somehow be as all-encompassing as possible and include, but not start with, the Greeks and Romans. Mimi and I worked on the line-up of poets from nearly thirty centuries and anywhere in the world. The number 30 began to preside over our efforts. In the autumn of 1998, at what used to be the Voice Box next to the Poetry Library in the Royal Festival Hall, a group of – as it turned out - some 30 poets and readers of poetry came together for the first afternoon of a thirty-week course which began with Heaney, travelled back in time to Homer in Week 16 and then returned to the present and Derek Walcott in Week 30. The course happened again in 2001, 2004 and 2007. The truth of its subtitle's claim to be Reading Poets Present and Past as a Companion to Writing was generously demonstrated by the poet Jemma Borg:

"It would be true to say that your classes and your enthusiasm have been a most important influence on me over the past few years - and when I write a poem now, I do try to hear it in your voice, as that helps me to know if the music is right. There are also poets you have introduced me to that have become quite important - though perhaps it is also hearing the sheer range of poetry that matters. For me, the special quality of your classes is the way you weave lots of threads together, as I'm sure you realise, but it is this which makes the poetry come alive in the air. After the last session, I even felt drawn to dust off my copy of Paradise Lost, feeling I could finally go to it with an emotional understanding". When I met Seamus Heaney at Little Gidding in 2009 and told him about Heaney to Homer and Back, he said: "I'm glad you came back!" . |

| "Our conversation's like a wild mustang, no one knows where it will take us; but thanks to Graham's skill at group management it never gets out of hand" (Polly Clarke) |

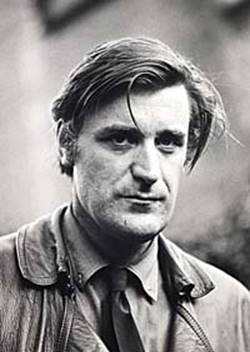

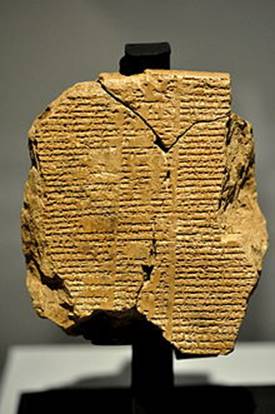

Hughes to Gilgamesh and Back (30 weeks)

|

Hughes, Plath,Seferis, Tsvetaeva, Frost, Rimbaud, Goethe, Basho, Donne, Petrarch, Rumi, The Battle of Maldon poet, Catullus, Pindar, The Epic of Gilgamesh poet, Sappho, Lucretius, Kalidasa, The El Cid poet, The Romance of the Rose poets, The Gawain poet, Ariosto, Spenser, Hölderlin, Barrett Browning, Apollinaire, Mandelstam, Bishop, Paz, Rich

(Images: Ted Hughes, The Epic of Gilgamesh Tablet V, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Adrienne Rich)

World Poets (30 weeks)

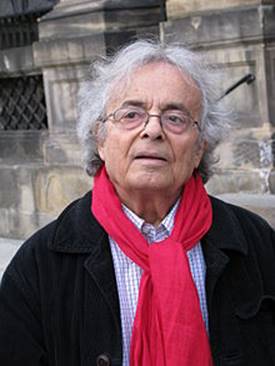

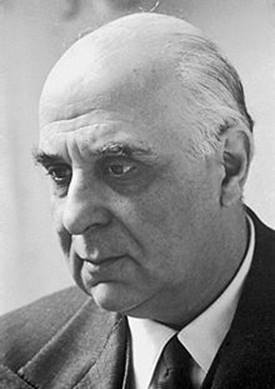

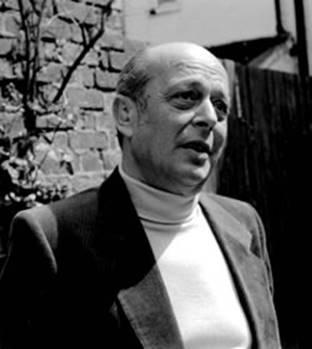

Adunis, Ariosto, Bishop, Donne, Dylan Thomas, Frost, Holderlin, Hughes, Lucretius, Plath, Rimbaud, Sappho, Seferis, Tagore, The Gawain Poet

(Images: Adunis, Bishop, Plath, Seferis)

More World Poets (30 weeks)

Octavio Paz (Mexico), Vénus Khoury-Ghata (Lebanon), Ivan Lalíc (Serbia), The Battle of Maldon Poet (England), Kalidasa (India), Mahmoud Darwish (Palestine), Wislawa Szymborska (Poland),

Li Po (China), Osip Mandelstam (Russia), Nina Cassian (Rumania), Catullus (Ancient Rome), Goethe (Germany), Fernando Pessoa (Portugal), African poets writing in Portuguese, Elizabeth Barrett Browning (England)

(Images: Khoury-Ghata, Lalic, Szymborska, Pessoa)

Inheritances (30 weeks)

Wordsworth, Japanese Women Poets 650 -1283AD, Herbert and the Metaphysicals, Hopkins, Petrarch and Montale – what happened to Italian poetry after Dante, H.D. and Marianne Moore, Holub & the mid-20th century Czech phenomenon, The Romance of the Rose, William Langland – what allegory did, Auden, Walcott and Poetry of the Caribbean

(Images: Wordsworth, Moore, Holub, Auden)

Inheritances We often know which poets of the past and present we feel indebted to and return to again and again, but what is that feeling of indebtedness all about? What does their poetry, and in particular their voice, do for us as writers or as readers of poetry, what has it given us, where did they ‘get’ it from ? Seamus Heaney has said that “craft is what you learn from other poets”, while Elizabeth Bishop was drawn to “the purity of language, which manages to express a very deep emotion without straining” in the poetry of George Herbert. In the 1930s everybody wanted to sound like Auden but how did Auden come by that sound ? And since Hopkins seems to sound like nobody else, does that mean he started his voice from scratch ?

This 30-week course, Inheritances, which is designed to develop and deepen the process of reading and discussion created by Heaney to Homer and Back and 2-week unit courses like World Poets, explores the work of ten poets, poet-groups or traditions, from Britain and beyond, for three weeks each, tracing where possible the progress of poets’ voices before, during and after their writing lives. It is intended that the course will help writers and readers of poetry alike to extend their sense of voice. |

Poets in The Front Line (30 weeks)

Andrée Chedid, Bei Dao, Tony Harrison, Guillaume Apollinaire, Agostinho Neto, Nazim Hikmet, Gabriela Mistral, Odysseus Elytis, Nelly Sachs, Octavio Paz, Yehuda Amichai, Edith Södergran,

Salvatore Quasimodo, Jean-Joseph Rabéarivelo, Antonio Machado

(Images: Andree Chedid, Nelly Sachs, Nazim Hikmet, Antonio Machado)

This 20th century course looks at the work of poets across five continents who found themselves and their work face to face with predicaments of war, injustice, imprisonment, radical change, exile and the written word, and used poetry to take on those challenges. |

The Poet’s Journey (20 weeks)

Auden, Barrett Browning, Basho, Bishop, Blake, Coleridge, Darwish, H.D., Lalic, Mandelstam, Neruda, Pushkin, Rich, Ritsos, Tsvetaeva, Wordsworth, Wyatt

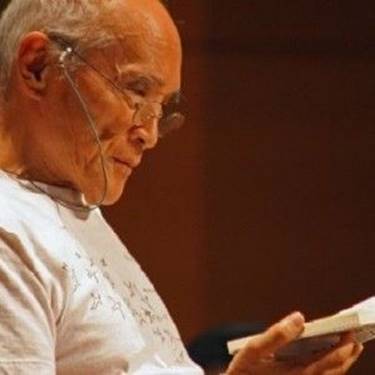

(Images: Basho, Darwish, H.D., Tsvetaeva)

This course chooses poems from Britain and abroad to illustrate how absence from home and the encounter with another place influence a poet’s journey through the inner and outer world. The course will take the shape of a journey and each session will leave the group with challenges for their reading and/or writing. |

Philosophies of Love - Mahabharata, Troubadours of Provence, Dante’s Purgatory(30 weeks)

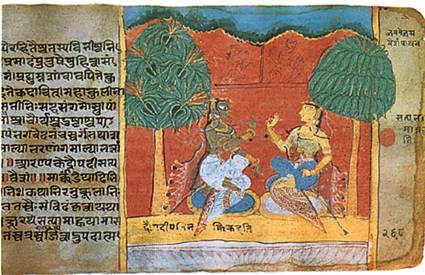

(Images: Ladies in conversation, detail from a folio from a manuscript of the Mahabharata, 1516; Arnaut Daniel, troubadour; Luca Signorelli, Dante and Virgil enter Purgatory)

Translating The Poem 1 (10 weeks)

Rimbaud, Apollinaire, Mallarme, Saba, Leopardi, Dante, Holderlin, Sodergran, Tao Qian and Darwish

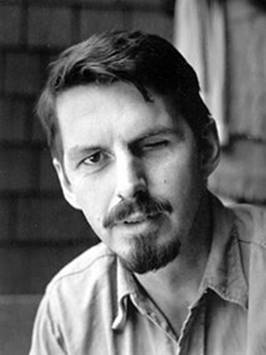

(Images: Rimbaud, Saba, Holderlin by Franz Carl Hiemer, Sodergran)

Translating The Poem 1 This 10-week course offers sessions on the act of translating poetry, the principles involved, and how translation may also provide new starting-points for, and ways of looking at, our own poetry.

The poems will be translated principally from French and Italian into English, with single additional sessions on translation from German, Swedish, Chinese and Arabic. Each week we will come fresh to the text for translation and experience the creative stimulus of decision-making: for this reason, the actual poems for translation will not be announced in advance and so no preparation is required. You will be able to work on your translation in class and be encouraged to complete it at home. The poems for translation will be (in order, week by week) by Rimbaud, Apollinaire and Mallarmé from the French first; then by Umberto Saba, Leopardi and Dante from the Italian; and, after that, by Hölderlin (German), Edith Södergran (Swedish), Tao Qian (Chinese) and Mahmoud Darwish (Arabic).

During the translation process each week, we will explore key translation issues such as how to decide when literal word-for-word translation should end and idiomatic alternatives begin, and at what point rhyme, metaphor, pun, and syllable-count should or should not be thrown out of the translator’s window – i.e. how do you tell the baby from the bathwater ?

Other published translations of the selected poems will be looked at in the second half of the lesson for comparison and discussion.

You need not have Italian or French to take part, as word by word support will be provided, although any familiarity you may have with either language would clearly be helpful.

You will need little or no knowledge of the other four languages to take part, as those sessions will be taught on that basis: once again, word-by-word support will be used in the interests of the main aim, i.e. an exploration of the translation issues presented by poems which will have been selected to offer the best chance of clarity, grasp, and, therefore, transfer. |

Translating The Poem 2 (20 weeks)

|

La Fontaine, Montale, Lorca, Celan, Szymborska, Neto, Arnaut Daniel, Khoury-Ghata, Ariosto, Neruda, Lalic, Sappho, Fischerova, Kalidasa, and six workshop sessions

(Images: Montale, Neto, Neruda, Fischerova)

Translating The Poem 2 This 20-week course explores the principles and practice of translating poetry. Poems will be translated; issues of idiom, metaphor, pun, rhyme, and syllable-count weighed up, and translations discussed in open workshops. You need not know other languages: 100% vocabulary support is provided in translating poems from French, Italian, Spanish, German, Serbo-Croat, Sanskrit, Polish, Czech, Ancient Greek, Angolan Portuguese, and Provençal. The workshops towards the end of each term provide an opportunity for presenting your finished translations to the group for discussion. |

Translating The Poem 3 - special edition (2 days - summer school)

|

De Nerval, Jaccottet, Horace, Menna Elfyn, Basho

(Images: Gerard De Nerval, Philippe Jaccottet, Menna Elfyn, Matsuo Basho

Translating The Poem 3 - special edition These two days of sessions to give you the practical experience of translating poetry reflect the growing popularity of the

Now, in four sessions spread over two days – open to all (you do not need to have attended Translating The Poem courses so far) – you will be given poems to translate from French, Latin, Welsh and Japanese. No previous knowledge of these languages is needed and the course are designed so that you benefit most by coming to each session unprepared.

Where vocabulary clues are not enough, and the grammar and syntax prove a mystery to you, you will be encouraged to respond transcreatively to the text, letting it take you where you will.

Published versions of the poems will be provided at the end of each session for comparison and discussion in the workshop sessions and there will be opportunities to read your finished and unfinished work.

|

Translating The Poem 4 (10 weeks)

Chedid, Pavese, Morgenstern, Pessoa, de Quevedo, Keller, Supervielle, Hernandez, Hauge, Rozewicz

(Images: Pavese, Supervielle, Hernandez, Hauge)

Translating The Poem 4 Translating Poetry is harder than it looks and easier than it doesn’t look. What on earth do I mean by that ? Well, it’s harder than it looks because we read it in the original or source language, and begin to think it in the target language, before the real work of composition begins. It’s easier than it doesn’t look, in the sense that once you’ve learned to give yourself a range of translation options for a word or phrase, over and above choosing the English word which most looks like the French or Italian or Spanish, you stop flogging the often dead horse of literal or mere mirror translation and start ranging more freely and calmly through a series of lateral thoughts, not forcing the French onto a sequence of words resembling it in English but letting English suggest how we might naturally say this ourselves.

Translation is a discipline just as writing is. It should, I believe, be lived like a mentorship, responding – as to a vocation – to any text which calls us. A text may call us in its original language, or cry out perhaps in the throes of being strangled by another translator’s heavy-handedness. |

Reading The Greeks (10 weeks)

Hesiod, Homer, Alcaeus, Sappho, Anacreon, Simonides, Pindar, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes, Menander, and poets of the Hellenistic World (Callimachus, Apollonius

Rhodius, Asclepiades of Samos, Leonidas of Tarentum)

(Images: Sappho (tondo fresco from Pompeii given her name), Euripides, Aristophanes, Apollonius Rhodius)

Reading The Romans (10 weeks)

Lucretius, Catullus, Vergil, Propertius, Tibullus, Horace, Juvenal and Ovid

(Images: Lucretius, Catullus at Sirmione, Horace by Anton von Werner, Ovid in Exile by Ion Theodorescu-Sion)

Reading Shakespeare’s Poetry (10 weeks)

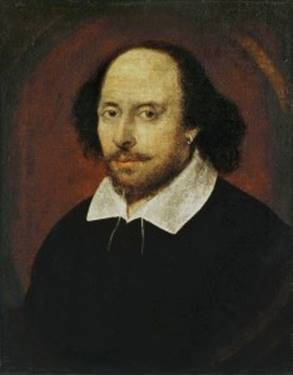

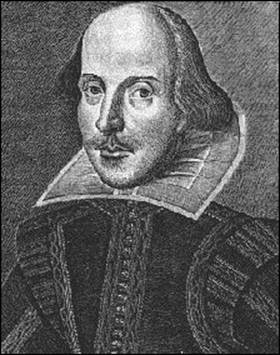

(Images of Shakespeare@ the Cobbe portrait (c.1610), the Chandos portrait (1600-10), the Droeshout portrait (1623)

Reading Shakespeare's Poetry Every latest portrait purported to be of William Shakespeare recharges imagination’s batteries as we look, perhaps finally at last, into his face for the first time and feel compelled to ask ourselves all over again so many things about him. Here's one: to what extent did the author of the Sonnets feel he was writing poems in his plays as though momentarily staging a poetry recital of set pieces to hold an audience’s breath in mid-drama? Over ten weeks, Reading Shakespeare's Poetry attempts to answer this very question, through the Sonnets, the longer poems ‘Venus and Adonis’, ‘The Rape of Lucrece’, ‘The Passionate Pilgrim’ and ‘Verses in Love’s Martyr’, as well as the poetry Shakespeare writes at key moments in the lyrical plays, the tragedies and the late Romances.When Postumus says to Imogen, “Hang there like fruit, my soul, /till the tree die” in Act Five Scene five of Cymbeline, the audience is in the presence of one of the best line-breaks in poetry. Yet when we go to see a Shakespeare play, the unfolding narrative, the constant impact of the action, and the naturalness of the verse as speech so take our minds off what Shakespeare is doing with it poetically, that much of the sheer craft of it simply sails over our heads. So what does distinguish Shakespeare poet from Shakespeare dramatist, how do the sonnets work, what relation is there between the longer poems and the plays, and where in particular may the plays be said to become poetry ? |

Reading The 19th Century (10 weeks)

|

Enter Tennyson, Wordsworth and Coleridge start walking, Up Hill and Down Dale with Coleridge, Odes and Visions - Keats and Shelley, Tennyson the Victorian, Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Dante Gabriel and Christina Rossetti, Were They Really Victorians? - the double enigma of Hopkins and Hardy

(Images: Tennyson, Coleridge, Christina Rossetti, Hardy)

Reading English Poetry - the first 900 years (10 weeks)

Caedmon, Bede, Beowulf, Cynewulf, The Vercelli Book (including Dream of the Rood), King Alfred, Genesis B, Judith, The Exeter Book(including The Seafarer), The Battle of Maldon poet,

Bestiaries (Physiologus) The Panther, The Whale, The Partridge, The Owl and the Nightingale, Piers Plowman, The Gawain poet (Patience, Pearl, Cleanness, Sir Gawain and the Green

Knight), Old English Poetry and the 20th century

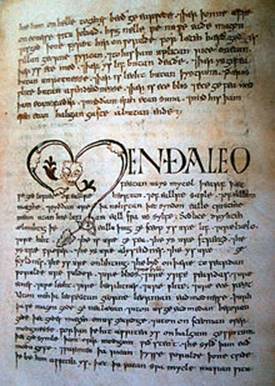

(Images: King Alfred in Winchester, 'The Dream of the Rood' in the Vercelli Book, Langland's Dreamer from Piers Plowman MS, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight from British Library Cotton Nero MS)

Reading English Poetry – the first nine hundred years Most poets of the last seven centuries have read and been grateful to Chaucer, but which poets did he read? The very idea that the Canterbury Tales was preceded by another nine centuries of English poetry may come as a surprise. Reading English Poetry – the first nine hundred years heads for the horizon of that surprise and stands among the Anglo-Saxons at the shoulders of Caedmon and Cynewulf at the start of an exploration of Old and Middle English Poetry in translation which charts a course through the heroic, elegiac and enigmatic worlds of the Dream of the Rood, bestiary poems about the phoenix, the panther, the whale and the partridge, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Exeter Book (which includes The Seafarer), Beowulf, The Battle of Maldon, Pearl and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Here are the foundations of English poetry, the fertile and ingenious seed-bed of so much of the English poetic tradition from Chaucer to the present day, in fully illustrated sessions on the work of English poets writing between the years 450 and 1375. |

Reading The French (10 weeks)

The path to Victor Hugo - De Béranger, Desbordes-Valmore, de Lamartine, de Vigny, Hugo; De Nerval, with de Musset, Gautier, de Lisle; Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Verlaine, Corbière,

Rimbaud, Laforgue, Apollinaire, and 20th Century Anthology Night (Saint-John Perse, Jouve, Eluard, Michaux, Prévert, Herlin, Jaccottet, Mansour,Bancquart, Supervielle, Desnos,

Char, Ponge, Frenaud, and Bonnefoy

(Images: Hugo, Verlaine, Apollinaire, Mansour)

From The Song To the Symphony (20 weeks)

|

|

Berlioz Nuits d’Été (Théophile Gautier), Benjamin Britten Les Illuminations (Rimbaud), Benjamin Britten Nocturne (Tennyson, Owen, Keats)/

Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings (Tennyson, Blake, Keats), Benjamin Britten War Requiem (Owen), Schumann Dichterliebe (Heinrich Heine),

Dmitri Shostakovich Fourteenth Symphony (Rilke, Apollinaire, Lorca), Luigi Dallapiccola Liriche Greche [Frammenti di Saffo (Sappho) Carmina Alcaei (Alcaeus),

and Due Liriche di Anacreonte (Anacreon)], Samuel Barber Dover Beach (Matthew Arnold), Tippett Songs for Ariel (Shakespeare), Schoenberg Gurrelieder (Jens Peter Jacobsen),

Sibelius Songs (Rydberg, Fröding, Josephson) + Luonnotar (Kalevala), George Benjamin A Mind Of Winter (W Stevens) and Upon Silence (Yeats),

Elliott Carter Three Poems of Robert Frost (Frost), A Mirror on Which To Dwell (Elizabeth Bishop), In Sleep, In Thunder (Robert Lowell), Gerald Finzi Dies Natalis (Traherne),

Intimations of Immortality (Wordsworth), Luciano Berio A-Ronne(Edoardo Sanguineti), Coro (Neruda), Oliver Knussen Whitman Settings (Walt Whitman),

Symphony No 2 (Sylvia Plath), Mahler Das Lied von Der Erde (Li-Tai-Po), Mahler Kindertotenlieder/Ruckertlieder (Friedrich Ruckert), Dmitri Shostakovich Suite on Verses of

Michelangelo Buonarroti/Benjamin Britten Michelangelo Sonnets (Michelangelo), Birtwistle Gawain (the Gawain poet + David Harsent), Nine Settings of Lorine Niedecker, Pulse Shadows

(Paul Celan)

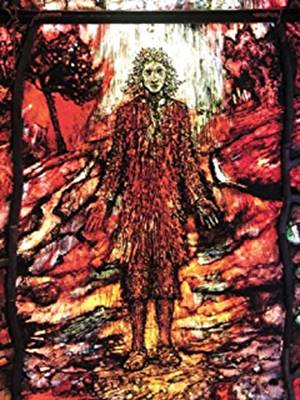

(Images: Hector Berlioz, Dmitri Shostakovich, Jan Sibelius, Gerald Finzi - top row

who set - second row - Gautier, Rilke, Rydberg, and Traherne here in one of Tom Denny's Traherne windows for Hereford Cathedral)

This 20-week reading and writing course looks at how poetry or poetic texts have been used by composers and asking, along the way:

Each week our discoveries, in the poem and the music, of the creative processes of poet and composer, will be used to prime your own writing. There will be audio illustration, but no knowledge of music theory or advance preparation is needed. |

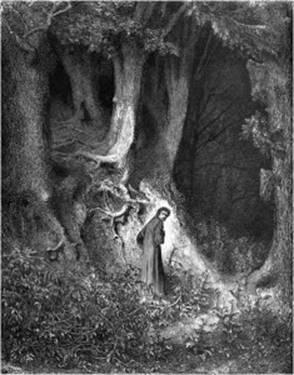

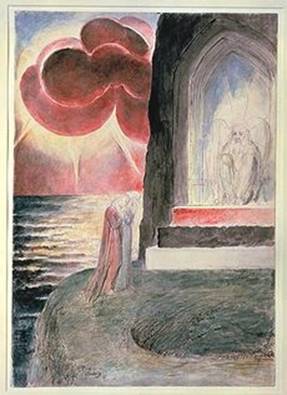

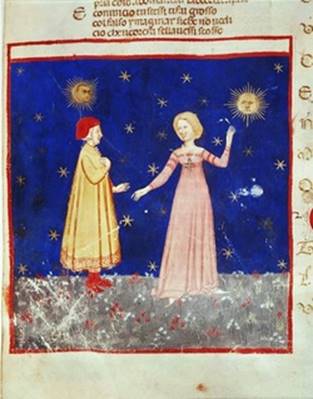

Dante’s Divine Comedy - text and art (10 weeks)

(Images: Dante Alighieri, attributed to Giotto (Bargello, Florence); Dante in the Dark Wood by Dore (Inferno, Canto 1), The Gate of Purgatory by Blake (Purgatorio, Canto 9), Dante and Beatrice prepare

for the ascent to Paradise, 14th century Venetian illuminated MS (Paradiso, Canto 1)

| Fresh from his acclaimed 15-month London supper lecture series on Dante’s Divine Comedy in 2010-2011, and using translations by John Ciardi, Dorothy L Sayers and some starry names from the poetry pantheon alongside the Italian text, Graham opens up this 100-canto poem of a unique journey through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise over ten weeks of close reading and discussion, illustrated by the paintings and drawings of Botticelli, Blake, Flaxman, Doré and others. |

Reading The East (20 weeks)

(Images: Zbigniew Herbert, Vasko Popa, Fadwa Tuqan, Forough Farrokhzad)

Reading The East (20 weeks)

Opening the Curtain (10 weeks)

Twice Fifty Miles With Wall and Towers Were Girded Round – the Berlin Wall goes up, but where is Xanadu ?

Poetry and Revolution 1905 & 1917 – Russia creates a New East

Wars and Afterwar(d)s - Poetry and the Iron Curtain

Modern Poetry in Translation and Poetry International

Drama on the South Bank – the Child of Europe readings in 1988

Beyond the Bosphorus (10 weeks)

Turkey, Kurdistan and Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, Palestine and Israel, Iran

|

In the first-ever issue, in 1966, of Modern Poetry in Translation – a fascinatingly flimsy small newspaper which would prove to be of unimaginable significance and historic promise for poetry and which you can hold in your hands in the British Library any time soon if you want to – its editors, Ted Hughes and Daniel Weissbort, wrote: “while we had material coming from many other areas of the world, it was that which came from Eastern Europe which was somehow the most insistent”. They then filled eight of MPT1’s ten newspaper pages with poems from “this region . . . at the centre of cataclysm”.

Leaf through the newspaper pages of MPT 1 – the newspaper format alone lacing the poetry’s bite as reportage from the front – and, after the lead coverage for Yehuda Amichai, sure enough you find yourself staring at more than two pages each of poems from Zbiginiew Herbert and Miroslav Holub, a column of Ivan Lalic, two columns of Czeslaw Milosz, nearly two pages of Vasko Popa, a page and a half of Andrej Voznesensky, all of it coming across to us like the variously hidden, encrypted or hand-held close-quarter camera work it was, by these poets from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Russia who were holding the door open, letting us see.

Hughes' and Weissbort's momentous editorial decision virtually changed overnight the eastward consciousness of British poets and readers by giving that East a voice in print and public which, first, it had never had before and which thendemanded our attention the more forcibly with the launch of Poetry International and the shock of the Prague Spring in 1968.

The exhilarating impact of those initiatives here in Britain will be re-created at the start of Reading The East, a brand new and fully illustrated 20-week 2-term reading course which will set out to chart, in poetry and time, the answers to four key questions of our time. What has East meant, and what does it mean now, for us? Where is it ? How has poetry in translation enabled us to encounter it ? And is ‘the Orient’ something different ?

Reading The East's Term 1 – Opening The Curtain – looked at the poetry of Eastern Europe, and Term 2 – Beyond The Bosphorus - introduced the idea of East in poems written by poets in the more distant Near and Middle East through the countries of the Levant and South-west Asia between the Mediterranean and Iran.

So why Reading The East, at the start of 2010 ?

World events were making it harder than ever to hold the East at arms’ length, overlook or underrate it. More properly aware of it than ever as a vast and multiple place, as small as a region or as big as a hemisphere, we began to realise that the East was neither merely the exotic curiosity we in the West once took it for, nor a blanket synonym for war, barbarism, danger and deprivation, all four of which the West too has always had in an abundance of its own.

In the last fifty years, from the Hungarian Uprising and the Prague Spring to the fall of the Berlin Wall, 9/11, the wars in Iraq and the invasion of Gaza, suddenly, in new ways as well as old, the worlds once behind the Curtain and beyond the Bosphorus demanded that we explore our assumptions about the East and pay unprecedented attention to some of its perspectives on us.

Increasingly the East seems to be demonstrating Eliot’s thought that perhaps ‘time future’ is ‘contained in time past’, our indivisibly shared single future, our divided past - a past in poetry whose span across millennia has been opened up to us only in that same half-century since 1956 to any lasting effect. 2009 has been the 150th anniversary of one of the greatest tunnellings into a foreign text, Edward Fitzgerald’s ushering of his readers into the Persian-speaking world through his translation of The Rubiayat of Omar Khayyam, and a salutary reminder of how poetry and translation can illuminate both the East and Western attitudes to it in ways that the most (and least) sophisticated news media can, and would, never aspire to.

Less than a hundred years ago, Arthur Waley and Ezra Pound brought three thousand years of life and thought in China into English. Rabindranath Tagore won a Nobel prize for writing poems set in a country, Bengal, which we still largely know only as the name of a sub-species of tiger. And Bloodaxe’s late 2008 anthology of Indian poetry describes itself as the first anthology to represent the major Indian poets of the last half-century.

For us in the West, the East is, at the same time, the Middle East. One of the gatekeepers to the East as we see it, and born in what was then the Western reaches of the Ottoman Empire and is now Thessaloniki, is a man whose imprisonment by his country for crimes of opinion helped produce one of the 20th century’s greatest poets in any language and one of the clearest voices of the oppressed, Nazim Hikmet. Poems of the Israeli Yehuda Amichai and the Palestinian Mahmoud Darwish (who died in August 2008) bestride the line of blood between their nations which both were alive to see drawn in 1948. Over the years of turmoil in Iraq we have been able to read Saadi Youssef and Zakaria Mohammed.

Will the poetries of Islam and Hinduism, the old and new war-zones, the theatres of military and social and ideological oppression, and the rising economic super-powers be the next build-up of work demanding to be translated and read by us if the global village is to get beyond a stalemate of cultural incomprehension, untrusting stand-off, and ignorance expressed as fear and recoil ? And will we be able to understand those poetries in English if we have not also traced their poetic forms and voices back to their roots in song, prayer, belief, thought, and systems of value ?

Reading The East devoted Term 1 to poetries from what was then behind the Iron Curtain, and in so doing re-live something like the full impact ofthat rush of poetic testimony from the world behind the Curtain in Eastern Europe starting in the mid-1960s. The newly created periodical Modern Poetry in Translation with Ted Hughes and Daniel Weissbort at the helm, and Al Alvarez’s editorship of Penguin Modern European Poets, brought us startling shipments of hitherto largely or wholly untranslated poems and unreported lives of the finest poets from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Serbia, Rumania, East Germany and Russia.

So, in parallel with world events of recent years and others as they happen, this twenty-week reading course charted the poetic revelations both old and new which have come to us from Eastern Europe, are still coming from the Near and Middle Easts, and still have the potential to broaden and deepen our reading and writing of poetry.

“The Berlin Wall had been an Iron Curtain” was how the BBC’s Brian Hanrahan put it as, on 9th November 2009 he re-lived the moment twenty years ago in 1989 when the Wall came down and, a year later, the Soviet Union had collapsed.

Of course, it had never been a real iron curtain, because real curtains don’t descend except in the theatre and then only for safety reasons, and in that speech in Fulton, Missouri on 5th March 1946 Churchill had clearly said that “from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent”. As a boy listening to the news on the Home Service, though, I remember trying to imagine, each time it was mentioned, which was often, how big the rings that held the iron curtain on its rail would have had to be.

But then, from news reports alone, how close could any of us in the West have come to understanding the nature of daily life on the other side of that non-existent curtain which so partitioned Europe by its very absence ? How else could we know the secrets of Eastern Europeans’ hearts and lives if not through what emerged along the extraordinary conduit of smuggled manuscripts and samizdat literature ?

And so we came to know that the poems, novels and plays of those times and countries contained ‘live’ evidence we may not, before, have read or known how to read or even, given the ‘unacceptable’ face of Communism here, cared to read, because the East had been an alien place that moved us, first and foremost, to step back thankfully from the idea of it, rather than head for the eye of its storm on the ready-made need-to-know armchair spy-planes of that poetry in new translations.

You might have been left wondering, after the 9th November 2009 celebrations in Berlin, exactly where the one thousand plastic-foam dominoes will be put now so that we may read the legends on them. So too - and as we become more aware of another wall of incomprehension, the same one that was built of our own fear and loathing of the Other many centuries ago along the Mediterranean and beyond the Bosphorus – we readers, who feel that, for whatever reason (including the pre-natal imperative), we did not do justice to the poetry of the Eastern bloc in those years, can perhaps now rise on the air-currents of commemoration and really delve into the poetic testimony of individual lives for the greater understanding they may always have been offering of what it meant to be born, to live, and to write, in the East behind the curtain. |

Graham also devised and led on-location days, including

|

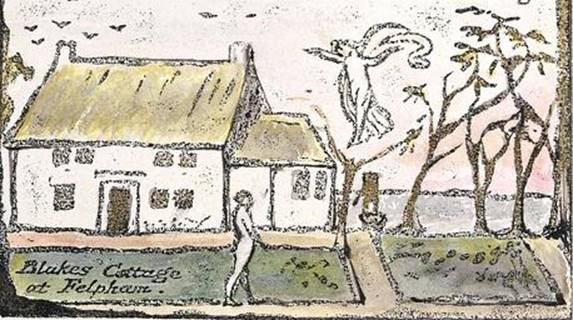

Blake in Sussex |

TO MY DEAR FRIEND, MRS ANNA FLAXMAN

This Song to the flower of Flaxman’s joy, To the blossom of hope, for a sweet decoy: Do all that you can or all that you may, To entice him to Felpham & far away:

Away to Sweet Felpham, for heaven is there; The Ladder of Angels descends thro’ the air; On the Turret its spiral does softly descend, Thro’ the village then winds, at My Cot it does end.

You stand in the village & look up to heaven; The precious stones glitter on flights seventy seven; And My Brother is there, & My Friend & Thine Descend and Ascend with the Bread & the Wine.

The Bread of sweet Thought & the Wine of Delight Feeds the Village of Felpham by day & by night; And at his own door the bless’d Hermit does stand, Dispensing Unceasing to all the whole Land.

14 September 1800 From THE GATES OF PARADISE |

|

Hardy in Dorset |

It faces west, and round the back and sides High beeches, bending, hang a veil of boughs, And sweep against the roof. Wild honeysucks Climb on the walls, and seem to sprout a wish (If we may fancy wish of trees and plants) To overtop the apple-trees hard by. Red roses, lilacs, variegated box Are there in plenty, and such hardy flowers As flourish best untrained. Adjoining these Are herbs and esculents; and farther still A field; then cottages with trees, and last The distant hills and sky . . . the opening of 'Domicilium' |

Hopkins in Oxford

Clare at Helpston

Milton in London and Buckinghamshire

Hughes and Plath in London

Eliot in London

Donne in London

Samuel Johnson (at his house) and Yeats & the Rhymers Club (at Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese) inLondon

the Brownings in London

Mallarmé in London

Yeats and Pound in London

Yeats and Pound in Sussex

Keats in London

Keats in the Isle of Wight

Coleridge in Highgate

Coleridge and Wordsworth in Somerset

Benjamin Britten’s Poets (Aldeburgh)

Benjamin Britten Les Illuminations (Rimbaud), Benjamin Britten Nocturne (Tennyson, Owen, Keats)/

Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings (Tennyson, Blake, Keats), Benjamin Britten War Requiem (Owen)

(Images: Tennyson, Owen, Blake, Keats)

Crabbe, Fitzgerald, and Tennyson in Woodbridge (Suffolk)

Opinions differ about what really happened, but according to at least one version, it was like finding a priceless painting stowed away in the attic. It’s a story to warm the hearts especially of translators and of people who like browsing in, and even more, in the boxes outside, bookshops.

Quite who it was that found copies of the first edition of Edward Fitzgerald’s translation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam in the penny box at Bernard Quaritch’s (the distinguished bookseller who had originally published the book two years earlier at a shilling) is open to question. Fitzgerald’s biographer Robert Bernard Martin credits a young Celtic scholar Whitley Stokes, who apparently bought several copies at a penny each and gave one to his friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Rossetti read the seventy-five stanza translation that evening. According to Swinburne, this next morning he went straight round to the booksellers where he bought several copies (the price had by then been raised to twopence) and gave them to his friends, including Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris and George Meredith.

The wheels were turning which would generate an unstoppable momentum: Fitzgerald’s Rubaiyyat was about to become one of the most famous verse translations into English of all time, hailed by John Ruskin who confessed that he had “never . . till this day – read anything so glorious”. It is hard to imagine anyone not wanting to reads on past Fitzgerald’s stirring first stanza: “Awake ! for Morning in the Bowl of Night Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight: And Lo ! the Hunter of the East has caught The Sultan’s Turret in a Noose of Light”.

As the action of Rubaiyyat is set, like Joyce’s Ulysses, over the space of a single day from dawn to dusk, we shall read from it on the hour through our day. Crabbe, Fitzgerald and Tennyson Day is an exploration of the life of Edward Fitzgerald with specially arranged visits to the houses where he was born and lived out his last years (including tea in his garden) and a walk through the fields to his last resting-place in the beautiful Boulge Churchyard, and a recreation of the period of the young George Crabbe’s apprenticeship and early writing life in Woodbridge, later to be commemorated in his outstanding poem in 24 letters, The Borough, and of the moment in the life of Fitzgerald’s great friend Tennyson when the author of In Memoriam came to visit him in Woodbridge. |

Robert Frost and Edward Thomas in Ledbury

A commission for one-day overviews of the poetry of different countries led to a series including:

Reading The Nordics

(Images: Edith Sodergran, Harry Martinson, Jens Peter Jacobsen, Tomas Transtromer)

| Through centuries of mythic and real time from the Norse Gods’ city of Asgard to Tomas Tranströmer’s Stockholm, Reading The Nordics explores a poetic heritage so rich as to stand comparison with those of Greece, Mesopotamia, India and China. Graham opens the poetry treasuries of Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Finland for a day of close reading and discussion of sagas, folklore, nature and supernature in poems from the Baltic-Finnish Kalevala song-lands and across ancient and medieval Scandinavia, and discovers the impact which this legacy had on twentieth century poets in these countries. |

Reading The Japanese

1. Japanese Olden Times

(Images: Princess Nukata, Ono No Komachi, Lady Izumi Shikibu, Matsuo Basho

2. Japanese Modern Times and the American Connection

(Images: Tanikawa Shuntaro; Amy Lowell, Adeline Crapsey, Robert Creeley)

Reading The Russians

(Images: Aleksandr Pushkin, Zinaida Gippius, Boris Pasternak, Anna Akhmatova)

Reading The South Americans

(Images: Cesar Vallejo,Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz)

Reading The South Americans It was not until novels like Gabriel García Marquez’s One Hundred Years Of Solitude hit the bookstalls of Europe and America in the mid 1960s that many of us woke up to the fact that Latin America had already been producing 20th century poets and fiction writers for fifty years and more. It is difficult to imagine how most of the West had managed so effectively to ignore, or at best give only glancing attention to, the work of the Peruvian César Vallejo, the Chilean Gabriela Mistral who was Pablo Neruda’s schoolteacher and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1945, Pablo Neruda himself, and the Mexican Octavio Paz, to name but four, until one has confronted, and shared some of the responsibility for, the tremendous and abiding condescension in the Anglophone West in the face of literature in any other language, let alone from a continent associated in the Western mind with conquest and subjugation.

To mention only one, Vallejo’s voice was authentically peasant and untutored, firing him not only to write wonderfully, both as a young man and in retrospect, about life in an isolated small town in the Andes, but also to experiment with form and pick up (even brandish) the theme-gauntlets of death, bereavement, dispossession, pessimism and despair. My father had done his best in the early 1950s to comfort me in my disappointment that Colonel P H Fawcett, author of Exploration Fawcett, who disappeared in the Mato Grosso in 1925 while looking for El Dorado, was not a direct relation. But then hearing that he had reported the spiders in those parts to be as big as dinner-plates made me glad he wasn’t and unburdened me of any direct family duty, once grown up, to go and find what was left of him. Conan Doyle’s The Lost World only heightened the sense of South America as an irresistibly magnetic theatre of life being played out on a spectacularly and exotically perilous edge stretching from perpetuated prehistory through the Conquistadores to the sensation unleashed in 1970 by the great Colombian novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s publication in English of One Hundred Years of Solitude adding the prospect of a continent in which magical realism was ‘normal’. Then came the moment in the guard’s van of a crowded commuter train speeding towards Florence in September 1973 when I opened Corriere Della Sera and read of the death of Pablo Neruda within earshot of the explosions which rocked the presidential palace in Santiago as Pinochet deposed Allende. I was hooked all over again. I hadn’t read a line of Neruda then, but knew his name as synonymous with poetry. He had wonthe Nobel Prize for Literature two years before. Neruda would be followed into the laureateship in 1990 by Mexico’s Octavio Paz, born, like Peru’s great César Vallejo, of Indian and Spanish descent. For the remit of Reading the South Americans day, I see Mexico, Cuba, and the countries of Central America like Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama as part of the South American (orLatin American) poetry story, united on the page by Spanish, and therefore the inheritors of, as well as declarers of independence from, the inevitable legacy of the poetry of Spain, and indeed of Europe. Reading the South Americanswill aim to touch down in at least some of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, and Venezuela,giving a deeper grasp of what it was like for these poets to have inherited such a history as theirs, and be writing in the midst of such a geography, when the national literatures were so young that they had to fight for an identity under the influence of Europe and what Neruda called ‘all the –isms floating above our heads’.We who love to read poems are more likely to learn about South America from their poetry than their history books. In particular, the new ‘takes’ these South American poets created make for riveting reading. Reading the poets of South America is like reading someone else’s letters from the bedroom, the barricade, the eagle’s-eye view, often all at once. Only in South America, it seemed, as though it were a feat of magical realismoffthe printed page, could Nicaragua’s liberation theologian poet Father Ernesto Cardenal become Minister of Culture as he did in 1979. The transatlantic phenomenon of Surrealism soon read like home-grown transplants, with Pablo Neruda a virtuoso of the genre.Neruda ispar excellencethe poet of the sea, not least because he travelled so much of it as a Chilean diplomat, but the bard of the continent’s dramatic hinterland sings all of its rivers and reaches the summit of his art inHeights of Machu Picchu, a 12-poem sequence in homage to the fifteenth-century Inca site not only completely – and very symbolically -undiscovered by the Spanish invader but unsuspected by anyone else either until the American archaeologist Hiram Bingham stumbled on it in 1911. Neruda was the poet of Chile’s and the whole continent’s history, a young poet of love who kept that flame going as he took on the hair-shirt mantle of politics as a poet, a senator, and an outlaw. As Neruda the Inca, so Octavio Paz echoed the legendary history of Mexico’s Maya civilisation; he too was a love poet and, in Spain for the Civil War, he too reported it in verse like a war artist. The voice is characteristically uncensored.Paz’s poetico-political fluency reminds you of someone like Amichai in Israel and Akhmatova in Russia but of poets of bygone ages in England. Then there’s CésarVallejo, Peru’s John Clare, but also her Lorca.And perhaps no poet drew South America in prose and verse more graphically and with such a playful sense of possibilitythan Argentina’s Jorge Luis Borges. So the comparisons with Europe are there to be made, but these South American poetries have emerged in and from their native cultures, transcending the attentions of the Iberian motherlands and creating galleries of writing which are both national and continental. I still haven’t been, but I’m taking the reading eye and ear there |

and of poets:

Reading Robert Frost

Dylan Thomas Day

Graham also took poetry writing seminars at his house in Holborn for fifteen years.

Poetry School Poetry and Autobiography downloadable courseby Graham FawcettGo to http://poetryschool.com/course-type/downloads |

Graham is available for Poetry School tutorials and e-tutorials. Call The Poetry School on 0207 582 1679.